‘A Perfect Turmoil’: Uncovering the life of Walter Fernald

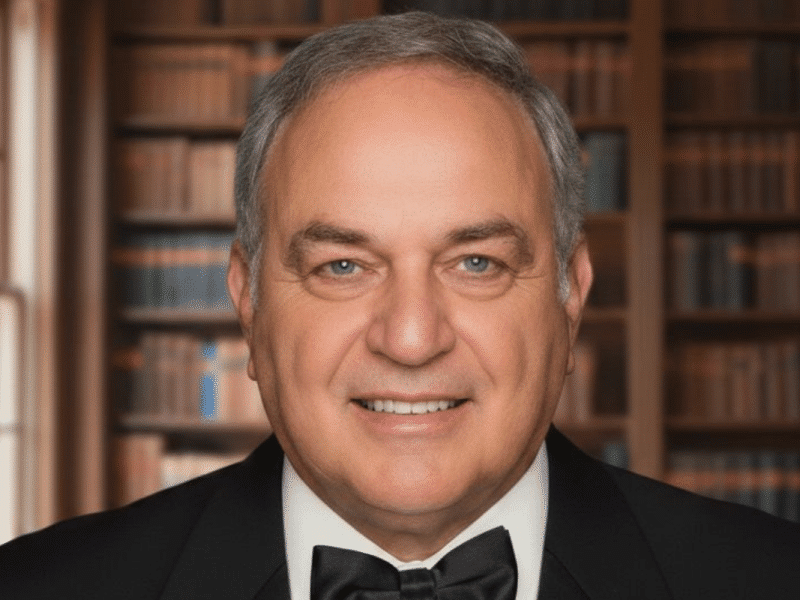

A new book by Waltham author Alex Green shines a light on a quintessential part of Waltham and world history that has been hidden away in archives for more than a century.

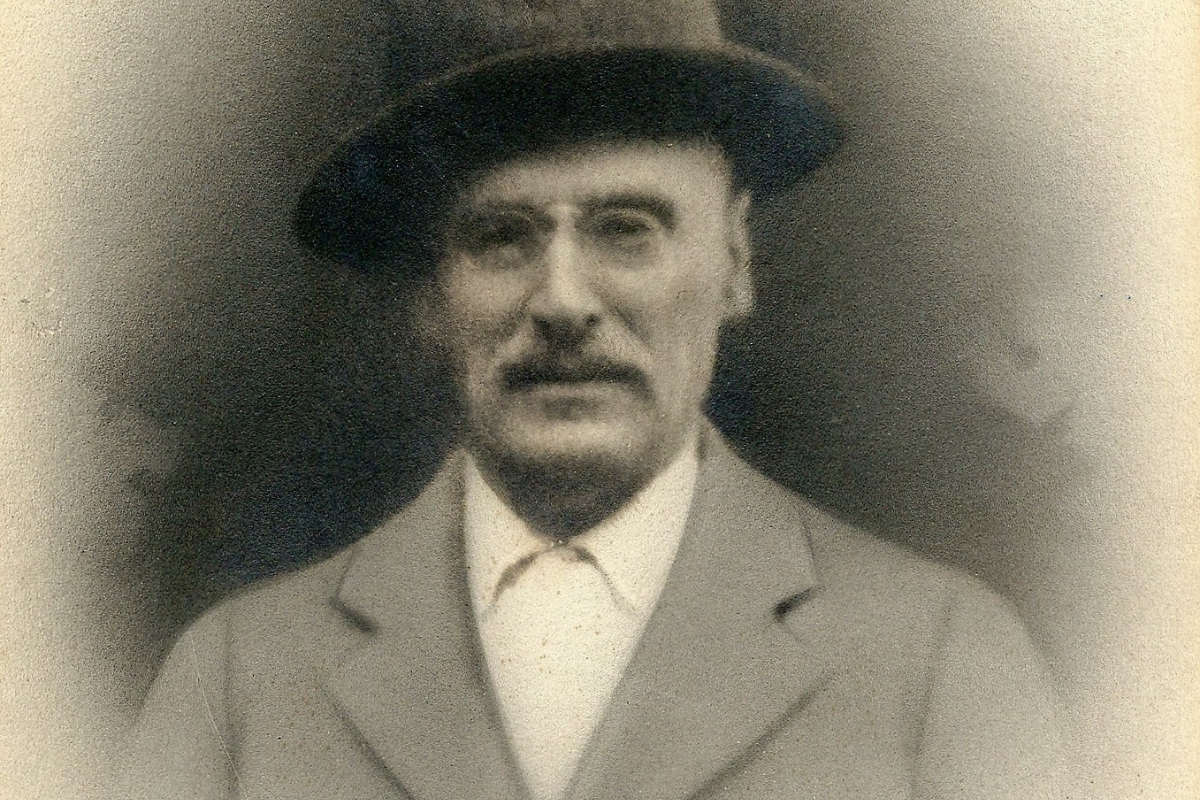

“A Perfect Turmoil: Walter E. Fernald and the Struggle to Care for America’s Disabled” tells the story of Walter E. Fernald, whose name is often now synonymous with abuse scandals that took place decades after his death, rather than his work as one of the foremost experts on disability and disability care in the world.

From defining disability and setting international standards for institutionalization to playing a role in the rise of the eugenics movement, Fernald changed the world as we know it. But the story of the man himself has largely been omitted from the history books.

Green spent more than a decade researching and writing his debut nonfiction book. Green, who teaches political communications at Harvard Kennedy School, is a visiting fellow at the Harvard Law School Project on Disability and a visiting scholar at the Lurie Institute for Disability Policy at Brandeis University. Green is also the author of state legislation creating the Special Commission on State Institutions. He now serves as vice-chair of the commission, which he said is the world’s first disability-led human rights commission on institutionalization.

In addition to unearthing and researching more than 250,000 unorganized original documents from the Walter E. Fernald State School, Green’s research included interviewing former patients and employees of the institution and politicians involved in its history, including former Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis.

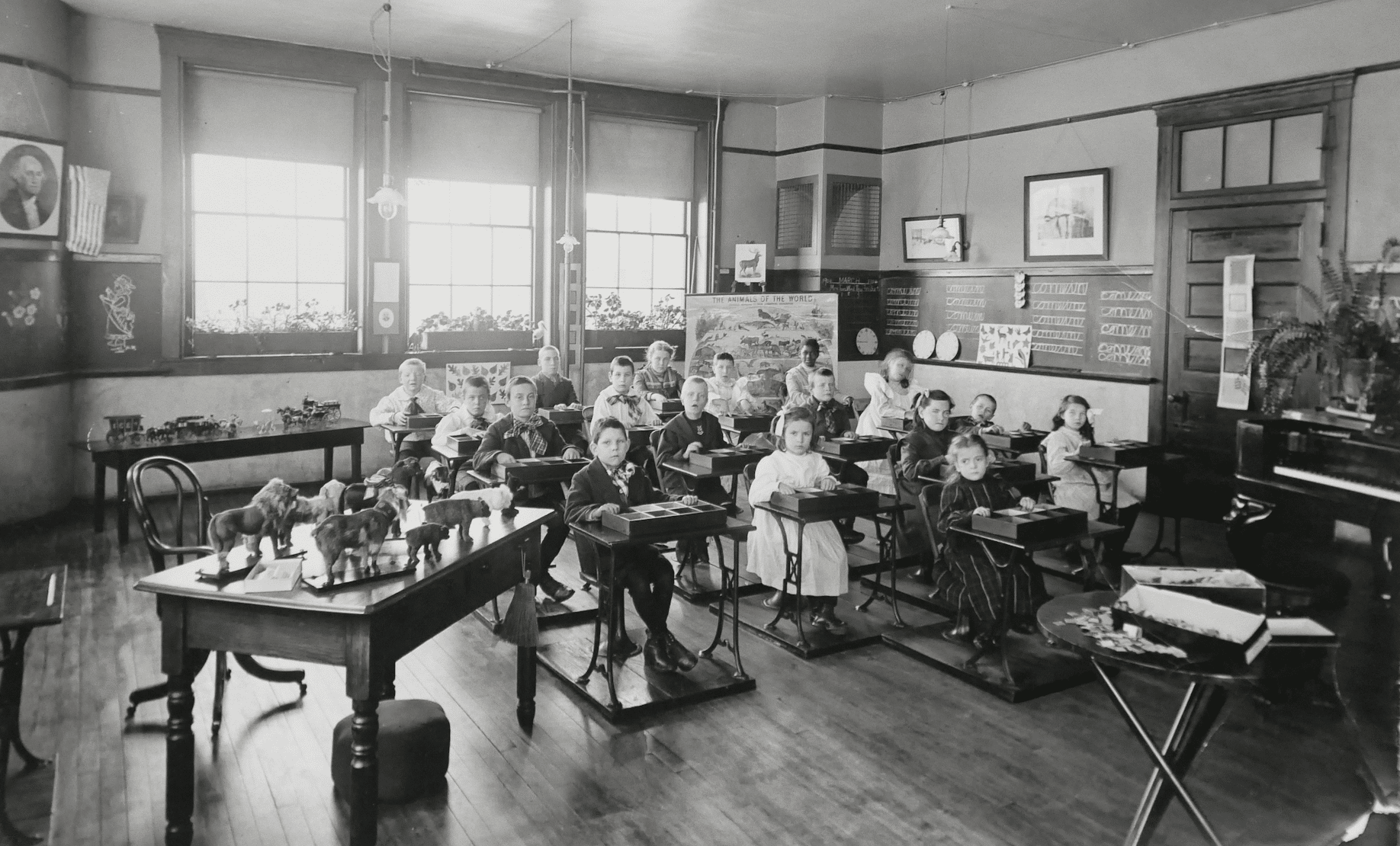

The school was founded in 1848 as the country’s first publicly funded school for people with developmental and intellectual disabilities.

The school moved from South Boston to Waltham in 1890, where it operated until the state shut it down in 2014. From 1887 to 1924, the institution was run by Fernald and became the epicenter of the study of disability and disability care.

When Fernald died in 1924 at the age of 65, the governor of Massachusetts ordered that flags around the state of Massachusetts be flown at half-staff in Fernald’s honor.

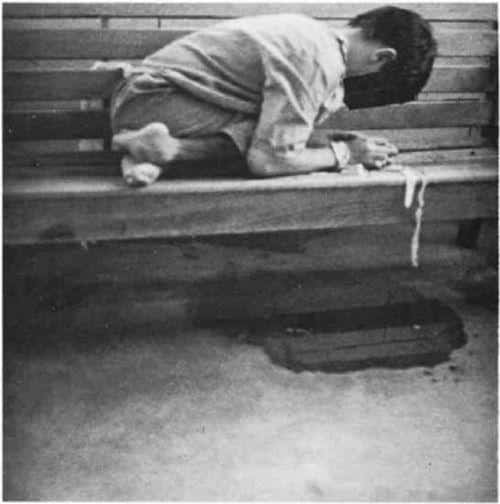

The institution came to infamy in modern society after an abuse case that took place in the mid-20th century when more than 100 children were fed radioactive iron and calcium without their knowledge. The experiment was run by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Quaker Oats.

‘A haunting of our collective conscience’

“The Walter E. Fernald State School is the most important historical site of its kind in the United States. The nation’s foremost institution for intellectually and developmentally disabled people, the school had a life span that stretched across an expanse of time from before the Civil War into the early twenty-first century. But for those who know its name, it does not stir thoughts of dates, places, or events. It is a threat, a nightmare, a deep-seated fear. It is a feeling. A place of shame. Its name is a provocation. It should be,” Green wrote in “A Perfect Turmoil.”

Green said Fernald built the institution in Waltham on a utopian hope of protecting the disabled from a world that was often cruel to them. But, he said, at some point Fernald’s perspective shifted and he began to feel that the world might need to be protected from the disabled.

Eventually, toward the end of his life, Fernald returned to his earlier beliefs, but much irrevocable damage had already been done. Among other things, Fernald’s 1912 publication “The Imbecile With Criminal Instincts” had become a major contribution to the birth of the eugenics movement.

Reckoning with the past

Green said he hopes his book can encourage conversation about how Waltham as a community comes to terms with and acknowledges the institution’s past.

In 2014, after the institution closed, the City of Waltham bought the property. Since then, the property has been the site of criminal activity, namely trespassing, vandalism and fires (including arson), while the city has planned and worked on the reutilization of the property.

Waltham Mayor Jeannette A. McCarthy said the property is being divided into five sections: a nature area, a memorial area, a “universal” area, a theatre/arts area and an athletic area. These plans have been controversial within the Waltham community and beyond.

Green said many cities with historic disability institutions rightly struggle to reckon with their histories. He said community members often have close ties with the institutions, whether as employees or patients, which can make grappling with difficult history especially challenging.

“I think it makes it a very painful thing to reckon with and there aren’t a lot of good roadmaps on how to do that. A lot of my work has been trying to show that the best way to do that is to have disabled folks, and particularly disabled folks who were in the institutions, really lead what a reckoning looks like,” Green said.

“We now know that Walter Fernald died believing that this institution that was later named for him, and all the other institutions like it, that he had helped build around the world, should be radically scaled down to almost nothing. And that what he cared most about was being a good community to our disabled citizens,” Green said.

Green acknowledged that in the last decades of the institution’s life, it became a much more positive place. He said employees made very earnest and caring attempts at bettering the institution.

Green also said that while that time and work should be recognized, this recognition should not come at the erasure of the suffering that countless disabled people experienced at the institution in its earlier days.

“For a large part of its history, this is an incredibly sorrowful place where disabled people were removed from society, often forcibly from their families, made to do enslaved labor to support one another, tortured, abused and left to die,” said Green.

Green continued: “The important message [Fernald] leaves the community to wrestle with is that the problem is not the disabled people — the problem is the non-disabled people and their views of disabled people.”