Museum talk on the Great Boston Fire captivates a Waltham audience

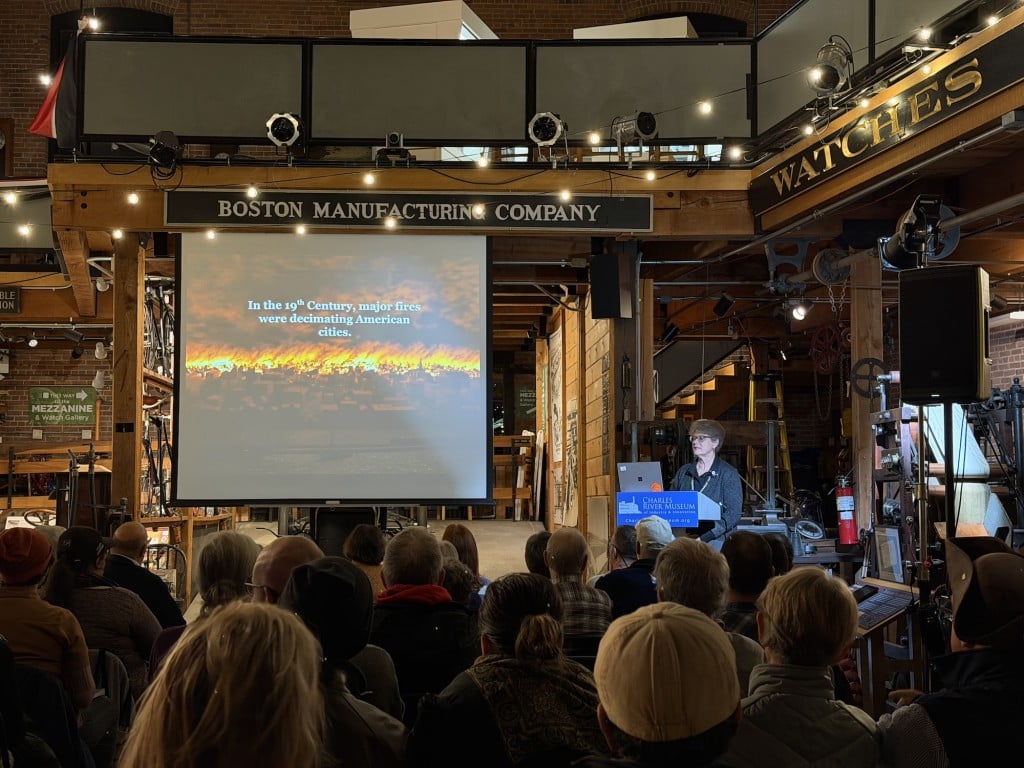

Boston journalist and author Stephanie Schorow brought the dramatic story of the Great Boston Fire of 1872 to life in a sold-out talk on Nov. 12 at the Charles River Museum of Industry & Innovation. The event, one of the museum’s Mill Talk series, attracted a crowd of historians, local residents and firefighters from Waltham and beyond.

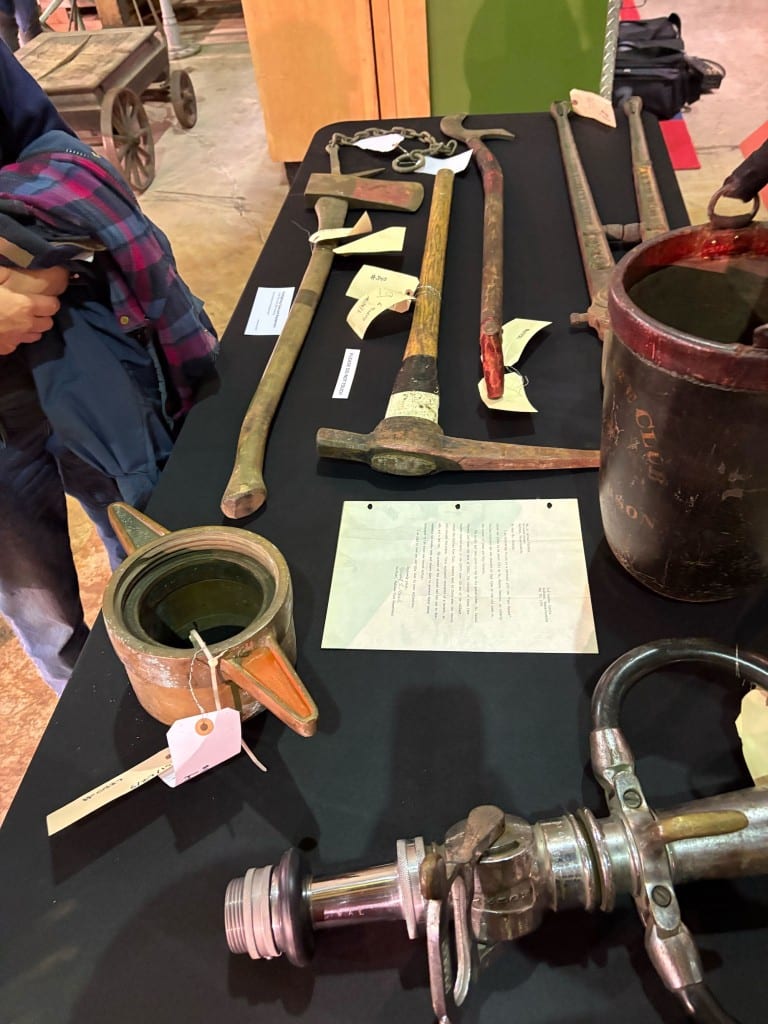

In conjunction with the talk, the museum showcased a treasure trove of firefighting artifacts, many dating to the early 1800s and drawn from the Waltham Fire Department’s archives. One highlight was the 1871 Amoskeag steam pumper — the city’s original “Engine 1 ”— which was used in fighting the 1872 blaze. Rushed downtown by rail, Engine 1 became an unforgettable part of Boston’s firefighting history and remains the museum’s most photographed artifact.

Schorow drew from her extensive research and her book, “The Great Boston Fire: The Inferno that Nearly Incinerated the City,” to illuminate a nearly forgotten catastrophe that reshaped the city’s identity. With photos, vivid descriptions and artifacts, Schorow recounted the fire’s history from the misguided decisions that precipitated it to the heroics of firefighters who fought it.

Over two days in November 1872, flames swept uncontrollably through Boston’s downtown, ravaging more than 65 acres, destroying nearly 800 buildings and leaving its population deeply traumatized. Schorow recounted how the fire ignited just past 7 p.m. on Nov. 9, 1872, in a dry goods warehouse on Summer Street and quickly intensified, driven by brisk winds and a lack of adequate fire safety infrastructure.

She described how Boston’s narrow streets, tightly packed wooden buildings and delayed alarms created a perfect storm of destruction. The presentation highlighted stories of heroism, such as volunteer firefighters who operated pumps through the night and residents who risked their lives to save neighbors and valuables. Period newspaper accounts underscored the immense scale of the devastation, which would spur future reforms to building codes, firefighting equipment and city planning.

Though the Great Boston Fire was one of the most expensive fires in terms of property damage in U.S. history, Schorow said it is less well-known today than its infamous predecessor in Chicago. She argued that examining moments of crisis such as Boston’s inferno offers valuable lessons for modern urban resilience, community strength and the importance of learning from history.

The museum’s collection

Gabriel Hurdle of Quinsigamond Community College played an instrumental role in helping the museum team identify, sort, and display its growing collection of firefighting artifacts. The collection features 19th and early 20th-century firefighting equipment, rare photographs and ephemera, much of which was donated by the Waltham Fire Department to the museum in 2018.

Other historic items, including the 1871 Steam Pumper – Waltham Fire Engine No. 1, which helped combat the Great Boston Fire of 1872 – were donated by the family of Waltham industrialist and collector W.H. Nichols during the museum’s founding years, and now serve as proud centerpieces in the main gallery.

The artifacts on display illustrate the evolution of municipal fire departments, showcasing their transformation from bucket brigades and hand pumpers to steam-powered engines, horse-drawn apparatuses and eventually motorized vehicles. The Great Boston Fire of 1872 was among several destructive urban blazes that swept across American cities in the latter half of the 19th century, emphasizing the growing need for modern fire departments, improved building codes and wider public awareness about the dangers of fire in densely populated communities.